Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches.

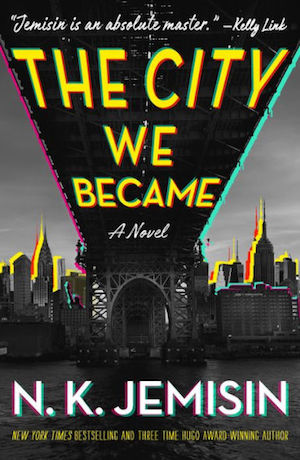

This week, we continue N.K. Jemisin’s The City We Became with Chapter 12: They Don’t Have Cities There. The novel was first published in March 2020. Spoilers ahead!

“There are wonders you can’t imagine. Convolutions of physicality and intellect beyond anything this world might ever achieve, but nothing so monstrous as cities.”

Chapter 12: They Don’t Have Cities There

At breakfast the morning after his attempted assault and Aislyn’s ass-whupping defense, Conall is much subdued. He’s regained favor with dad Matthew, however, by claiming the backyard mess resulted from his heroic struggle with an intruder. In the Houlihans’ front yard, a twenty-foot-wide white cylinder rises out of sight. Like the flower fronds and Woman in White, the pillar’s Not From Around Here, for only Aislyn can see it. On the horizon, somewhere near Freshkill Park, another pillar rises.

Aislyn gets into her car, which Matthew helped her buy and in which he’s probably hidden a tracking device. Aislyn takes the bus when she wants privacy. Today she’s just headed for the library job Matthew got her by “losing” outstanding parking tickets for the head librarian. Instead of driving off, she ponders the strange turn her life’s taken. In the rearview mirror she glimpses a barely-there white tendril and asks the Woman to come—Aislyn really needs to talk.

A vast shadowy space replaces the driveway in the mirror. One shadow shifts into the Woman, white as ever but more “exotic” in her features. When Aislyn points out her baldness, the Woman obligingly grows a mane of white hair. She sort-of apologizes for the bad behavior of her “minion” Conall, but after all the tendril “guide-lines” don’t control people. They just “encourage pre-existing inclinations, and channel the energies from same into more compatible wavelengths.”

Aislyn’s reminded of ants infected with behavior-controlling fungi. The Woman, not liking this comparison, shoots out of the mirror as a “thick tongue of featureless white substance.” It transforms into a “pixellated” figure, then a “realistic” Woman. Three things keep Aislyn from screaming. First, she’s been taught to associate evil with dark skin, ugliness, men. The Woman’s the opposite of these things. Aislyn knows her form’s a guise, but she looks all right. Second, if she screams and her father comes to defend “what’s his,” the Woman may implant a “parasite-flower” in him, increasing his inclinations toward violence and control. Third, Aislyn is lonely.

The white cylinders, the Woman explains, are “adaptor cables” meant to adapt her universe to Aislyn’s. Now drive, and the Woman will explain further.

Aislyn drives. At first the car seems lower-slung, overweighted. “Damned gravity,” the Woman says, then adjusts her presence to compensate for a different universal “ratio.” As for the “cables,” the Woman’s putting them wherever Aislyn’s “rejected this reality to some degree.” When she’s put up enough adaptors… but Aislyn’s “place is so primitive!” How can she explain the situation when Aislyn barely understands how her own universe works, much less others!

Oh well, she’ll try. Nowadays there are “ex-approaches-infinity-llions” of universes and more every minute. Once there was only one universe, “where possibility became probability, and life was born,” so much life everywhere, unlike Aislyn’s “stingy universe, where life huddles on a few wet balls.”

Aislyn’s distracted from the road by the changing images in her rearview mirror. Instead of other cars, she sees the empty shadowland again. Pink vapor darts across it like a living thing. Then a black roundness like a hockey puck scuttles in. Black is bad, but the puck is “kind of cute,” even as it erases the pink vapor, making it gibber with pain and despair.

For all the first universe’s “convolutions of physicality and intellect,” the Woman continues, it had no such monstrosities as cities. Aislyn agrees that cities are monstrous: filthy, overcrowded, full of criminals and perverts, environmentally destructive. She dislikes being one now herself. But the Woman goes on. The problem with cities is they’re “rapacious,” invasive. They “punch through” other universes, instantly destroying thousands of realities. And they can do worse.

The puck in the mirror lingers, and a waft of cold air chills Aislyn’s neck. The Woman asks if she’s read Lovecraft. A little, Aislyn says. “The Horror at Red Hook” is her favorite; Lovecraft’s description of Brooklyn echoes her father’s as being “full of criminals and scary foreigners, and gangs of foreigners being criminal.”

Lovecraft was right, the Woman says. Put enough people in one place, different “strains” exchanging cultures, and “hybrid vigor” results. Cities bring multiple universes together, and such breaches weaken the “whole structure of existence.” Countless people, worlds, galaxies, are “crushed beneath the dread, cold foundations of [Aislyn’s] reality,” and she doesn’t even hear their pleas. Is that fair? Does Aislyn understand why the Woman has to stop her?

Buy the Book

Africa Risen

Aislyn understands that such a situation would be awful. Can’t all the realities coexist? It’s been tried, the Woman sighs, but –

A weird “Da-dump” sounds behind Aislyn. Midturn, suddenly heavier, her car lurches into the curb, then rebounds toward an oncoming car. Aislyn manages to avoid a crash. The Woman snaps at something that she told it to “stay in the staging area.” A door closes. The cold draft ceases. The car returns to normal, Aislyn parks in the library lot. She can’t have the Woman following her into work—can she call her another ride?

Aislyn’s so thoughtful, the Woman says. She hopes Aislyn knows she cares about her and wishes circumstances were different. “Belief matters in the multiverse,” and the Woman, like Aislyn, craves trust.

Aislyn’s heart goes out to the Woman, so sincere in her good intentions. She can’t “reconcile the big, elaborate topics” like multiverses and inevitable doom with “the simple reality of the Woman” being “a genuinely nice person.” “It will be all right,” she reassures her.

“You’re a good dimension-crushing abomination,” the Woman says, smiling. She vanishes, leaving Aislyn wondering why she smells ocean brine. But she’s late, so she must accept what she can’t understand and hurry into work.

This Week’s Metrics

The Degenerate Dutch: Aislyn’s learned from her father to “associate evil with specific, easily definable things. Dark skin. Ugly people with scars or eye patches or wheelchairs. Men.”

Weirdbuilding: Cordyceps fungi are truly our most accessible local example of cosmic horror.

Libronomicon: Aislyn works under the table at a library. She mostly likes romance, but has been introduced to Lovecraft by a senior librarian. She finds “The Shadow Over Innsmouth” rambly, but “The Horror at Red Hook” entirely in keeping with her father’s descriptions of Brooklyn, and the protagonist sympathetic due to being Irish and afraid of tall buildings.

The Woman in White, impressively for someone seriously not from around here, has also read Lovecraft.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Here we are again at those central questions of horror: What’s scary? What should we do about it? And how badly can we screw ourselves over if our answers to those questions are very, very wrong?

Confirmation bias is a bitch. And also an instrument that the Woman in White plays like Yo-Yo Ma plays the cello.

Not much happens in this chapter—except that a lot happens, and confirmation bias lets it happen without the dramatic confrontation that it deserves. The Woman, as the text underlines, gets around Aislyn’s xenophobia and paranoia simply by looking white, able-bodied, and female. By being nice. The thing about phobias is that they are not actually an effective replacement for healthy risk assessment. So, without any of her trained fear triggers going off, Aislyn believes the Woman when she shouldn’t, and brushes away things that should terrify.

Some of those things are terrifying for us: from a purely selfish perspective, the grand scale view of the cosmos is not enough to render human extinction trivial. Also, for what purpose might one need a transdimensional power adapter, and might it be at all related to the above triviality? It probably isn’t for charging your phone. (Unless your phone has some really disturbing apps. Um.)

Some of those things are terrifying about us: in case last chapter didn’t sufficiently rub in our eldritch nature, the Woman both reiterates the destructive power of city-births, and talks about how the sapients of other universes react. They cry out, but we don’t hear. They fight or flee. They worship, in hope of mercy, and we don’t even notice. You might get a better deal from Cthulhu, or at least from Nyarlathotep.

When she’s not just chalking the whole thing up to indigestion, Aislyn’s reactions are interesting. She has some intimation that not only do we all live at the cost of death or harm, but that it’s nearly impossible to avoid. Even for vegans. Presumably even for sapients living in places where they don’t have cities. She’s dismissive of harm beyond her immediate perception, but it’s a dismissiveness right on the edge of nuanced wisdom. After all, we don’t spend a lot of time regretting the Great Oxidation Event. If only she could get over the “Horror at Red Hook” view of Brooklyn, she might effectively consider strategies for minimizing the real harm being done.

She has a lot of practice dismissing signs of poorly-practiced affection, of course. After all, her father is the one who monitors her gas mileage and probably has a tracker hidden in her car. Controlling jackass—but that’s easier to get your head around when you haven’t lived your whole life dealing with it. It feels like she’s only just starting, without quite facing his abuse head-on. And she’s lonely, and—as scary as anything else here—the Woman is the closest she’s come to friendship.

The Woman, on the other hand, is nuanced right up until the point where she gets dismissive. She chatters, in friendly fashion, about destroying Aislyn’s species. She mentions that co-existence has been tried, but seems entirely uninterested in details that might suggest how and why it failed. She neglects local laws of physics, making herself a truly terrible car passenger. (Though I do often have to remind my kids, when they’re stowing spillable luggage, that they’re still in a gravity field. Sometimes being born here doesn’t help.) She calls Aislyn a friend, but doesn’t leap past the “isn’t it interesting” stage of noticing our commonalities.

And yet, I suspect that she’s lonely too. Maybe even lonely enough to provide a shred of hope for another way?

Anne’s Commentary

Confirmation bias is a bitch, all right—Jemisin foreshadows that Aislyn will realize this “much, much, much later, when the whole business is nearly over.” Aislyn will have never thought a truer thought, I say.

In the present story time of Chapter Twelve, however, Aislyn expends enormous mental energy confirming her biases. Can we wonder at this? In the past couple of days her reality has been turned upside down and inside out. She was a singular human female; now she’s a city, containing multitudes. She’s been schooled to think herself particularly vulnerable; now she wields superhuman power, the strength of her whole island. She has felt isolated, agonizingly lonely; now she has a friend—doesn’t she? Yes, she does. Of course she does. The Woman in White, the Woman Who Is Practically Whiteness Personified, can’t be bad, because White is Good. In addition, she’s Pretty and Female; it’s the Ugly and Male that are Bad, or at least suspect. And the Woman shows up when invited. The Woman listens. The Woman explains things. The Woman cares about her, “dimension-crushing abomination” though Aislyn is.

Because Aislyn is a good dimension-crushing abomination. It’s so important to be good when there’s really, essentially, no middle ground between Good and Bad, no shaded gray between White and Black (or Brown.) Or there shouldn’t be middle grounds and shades of gray—they make life so confusing! If you can’t readily separate the safe people from the dangerous ones, how are you supposed to protect yourself, or as importantly if not more so, believe you can protect yourself?

Belief is a critical concept in this novel. In the previous chapter, Bronca has told the other city-avatars that all the worlds humans believe in or imagine vividly enough come into existence. When enough humans occupy one space and tell enough stories—spin enough beliefs—about it, when they create enough layers of belief-realities—enough culture—a city is born. Great, right? For the city maybe, but its birth utterly obliterates every universe it punches through. In the current chapter, the Woman describes a similar process. Enough humans in a specific locality, layering their cultures into a critical mass, will birth a city. And the result? “Galaxies crushed beneath the dread, cold foundation of your reality.”

On the macro-scale, then, belief-become-reality is the ultimate danger, creating such breaches that “the whole structure of existence is weakened.” The Eden of existence, the Woman tells Aislyn, is the first universe, the “one realm where possibility became probability, and life was born,” life in an abundance unimaginable to one in Aislyn’s “stingy universe.” In the first universe, there are no cities. To the First-Universers—of whom the Woman is one, I assume—nothing is more “terrifying and terrible” than the city.

On the micro-scale of the discrete person, belief is similarly dangerous. Assume every brain might be like the Woman’s “first universe,” open to every “convolution of physicality and intellect,” not constricted by dispassionate observation, facts, knowledge. Those would be beliefs like Aislyn’s in the benignity of all things White, Pretty, Female. Of things that by those criteria “look all right.” Aislyn has proof through observation that the Woman in White is “just a guise,” an entity that can assume any form that suits itself and the prejudices of its targets. Either positively or negatively—notice that the Woman in White persona is ingratiating to Aislyn but provoking to the other city-avatars.

I’m afraid the human tendency to believe what we want to believe, even in the face of evidence to the contrary, will prove our species’ fatal flaw. It’s also one of our most powerful strategies for emotional defense, as Aislyn demonstrates in her adherence to Matthew’s worldview even as she increasingly realizes her protector Daddy is unadmirable, violent and controlling.

It’ll be no comfort to the other avatars (or humanity in general) if Staten Island shrugs off dependence on Matthew for dependence on the Woman. As of this chapter, Aislyn’s not ready to “challenge her own belief that the Woman in White isn’t so bad” or to “question her own judgment and biases and find them wanting.” Not given “how hard she has fought lately to feel some kind of belief in herself.”

If it’s belief in herself Aislyn can continue to fight for, though, I’m hopeful. The borough of Staten Island has chosen her self as its champion, and can that mean she, and it, aren’t worthy of joining the other boroughs in the quest to save New York?

Oh, and is Staten Island still floating out to sea? No one in this chapter seems to have noticed, or maybe they’re just believing what they want to believe. Or—maybe what they want to believe is that SI is divorcing itself from scornful NYC altogether, and that’s what’s powering the separation?

The power of positive—or negative—thinking ain’t to be sneezed at.

Next week, Carlie St. George’s Shirley-Jackson-nominated “Forward, Victoria” introduces us to a ghost with work to do.

Ruthanna Emrys’s A Half-Built Garden is now out! She is also the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, weird and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.